Long story short, Persistence

December 4, 2023

Shanna Daly

In this post I am pulling parts out of a talk that I did called “Long story short”. I delivered variations of this talk online for NZITF and the ICSL MRE webinar series in 2022 and also in person at CRESTCon 2022 in Canberra.

I found these interesting at the time as they were novel to us (back then), and that a lack of detection and response capabilities enabled this threat actor to carry out their activities unhindered. For a long time.

Dwell time is the length of time a cyber attacker has free reign in an environment from the time they get in until the time they are eradicated. —- depending on which report you read, the average GLOBAL dwell time for an attacker is between 160 to 200 days. Comparing that to when Mandiant published their first M-Trends report back in 2011, when the average dwell time was 416 days.

Hoorah, the average is getting less, that’s a good thing right?

Ransomware enters the room

The Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) continues to observe the targeting of Australian organisations by ransomware operators. This includes Healthcare and Medical Industry, Financial Services and Markets, Higher Education and Research, and the Energy Sectors. Between 2019 and 2020, ransomware attacks rose by 62 percent worldwide and with notoriously low dwell times, ransomware attacks are bringing the global average down.

But …. I’m not going to talk to you today about ransomware. I am here to talk to you about an attacker with a dwell time of over 981 days. I’m going to talk about persistence.

Once upon a time, in a land not so far away (and not so long ago)… #

981 days, that’s a lot of time to be able to get things done. I will however focus on a couple of key takeaway points:

- It can be very helpful to understand past exploits and techniques when looking for new ones: While these IOCs are techniques might be considered dated now, we often see a reoccurrence of techniques if vulnerabilities are not fixed, and we often see ransomware operators, who likely do not have a stash of zero days themselves, but they are very quick to jump on found vulnerabilities and capitalise.

- Follow your nose, or your gut when conducting investigations: Use your instinct and experience to dig a little deeper to find attacker activity. While many adversaries might not “dwell”, many do, and increasingly the methods of exploitation and attack are crossing over from nation state right through to more opportunistic attackers and everything in between. While the obvious might be easy to find and easy to think that the work has been done, but unless an attacker’s access has been completely removed from an environment, any remediation work may be for nothing as they’ll just pop back in undetected and re-establish their foothold. The malware in this post could have been easily missed if it wasn’t for the curiosity of the team to dig deeper when something didn’t look quite right.

Initial access #

When we begin any investigation my hopes of identifying how an attacker got the initial access into the network are in the realm of zero to none. This usually comes down to the available evidence, such as log files, on a system. In this instance my hopes met that expectation.

As you can imagine, 981 days is a lot of time to pass where evidence may be over written, or not written anywhere at all. We do the best we can with what we have to piece together the most likely entry point, or the likely vector of attack. What we did know however, was that this organisation had been notified by a third party of malicious behaviour to their external systems, specifically a remote access server (RD Server).

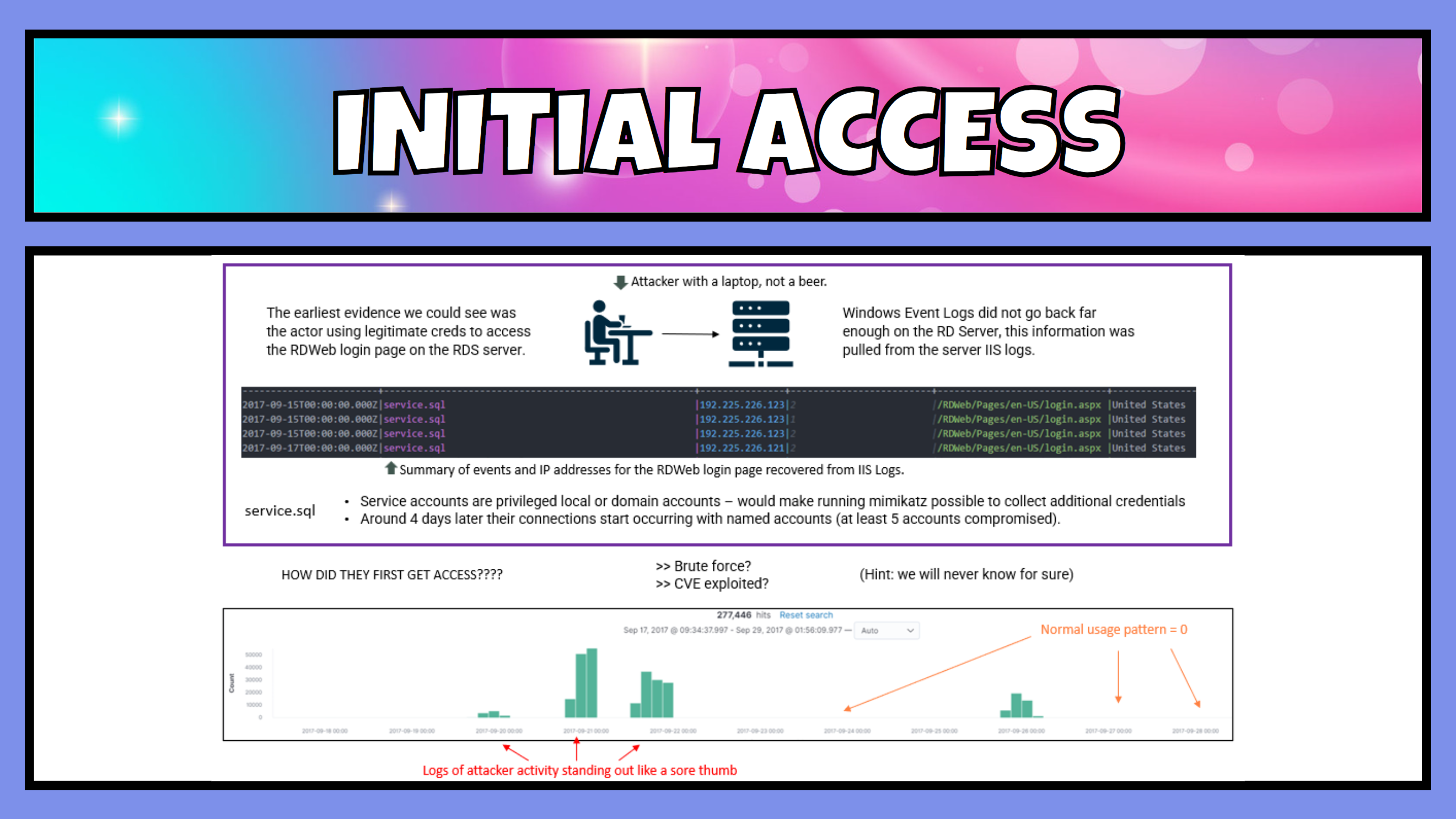

The RD Server was where we started and where we found what was to be the earliest evidence of a breach of that system – September 15, 2017, we will call this Dwell Day 1. The logs we had available to review were the IIS web server logs (LUCKY) from that system that showed the accounts logging into the RD Web login portal. RDWeb installation requires the installation of IIS services. This is why we were able to utilise the IIS logs to find login data.

Drilling down into the logs, we found that the first account that the attacker got a hold of was a service account, “service.sql”.

In these logs we also saw that a threat actor made a total of 277,446 connection attempts to the RD server between Sep 18 and Sep 29, 2017. Not a normal usage pattern and indicative of an account brute force attack, or maybe several, against that host.

We saw at least 5 additional domain accounts were successfully breached in this way.

What were the obvious things we looked out for here?:

- It should not be normal practice for a user to log into a system with a service account, let alone establishing a remote connection. Service accounts should be prevented from logging in locally or remotely. Searching logs for service accounts could reveal a weakness in the security of a network.

- Understanding what looks “normal” on a network and what usage patterns looks like might help to identify anomalies and peaks of activity like the ones shown should be investigated.

- The originating IP address was hosted out of the US, and lets face it, just looks suss. This does not look like it would be legitimate business behaviour for this organisation.

While having the IIS logs did help us identify the timeline of activity of external activity, there was no availability of Windows EventLogs, particularly the security event log, terminal services, scheduled tasks and SMB logs that would have potentially shown additional information around the attacker’s activities and any lateral movement. Also consider that attackers can and WILL delete event logs, this attacker did, so they should be backed up to an external logging source regularly.

Persistence #

Then the fun begins.

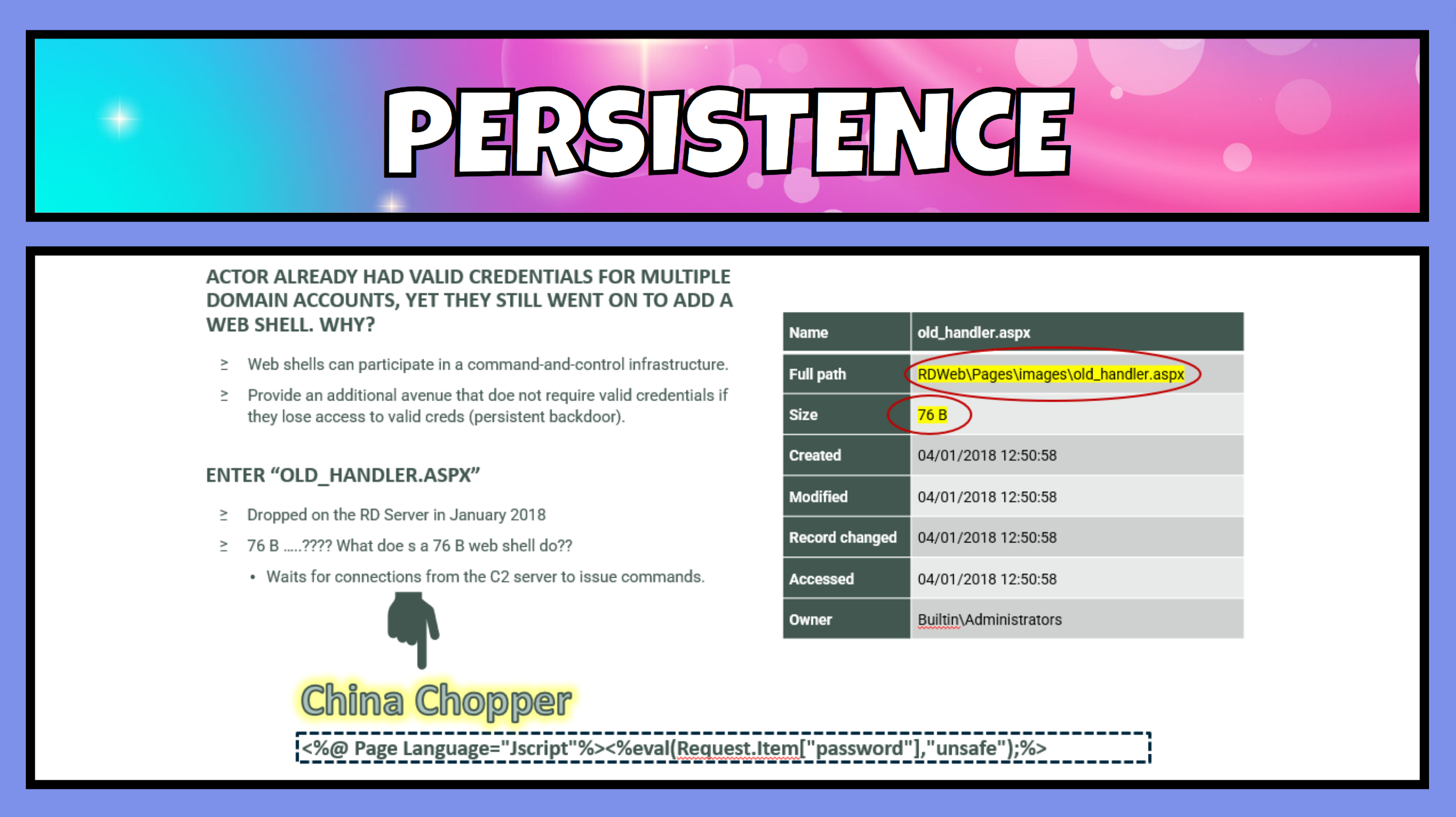

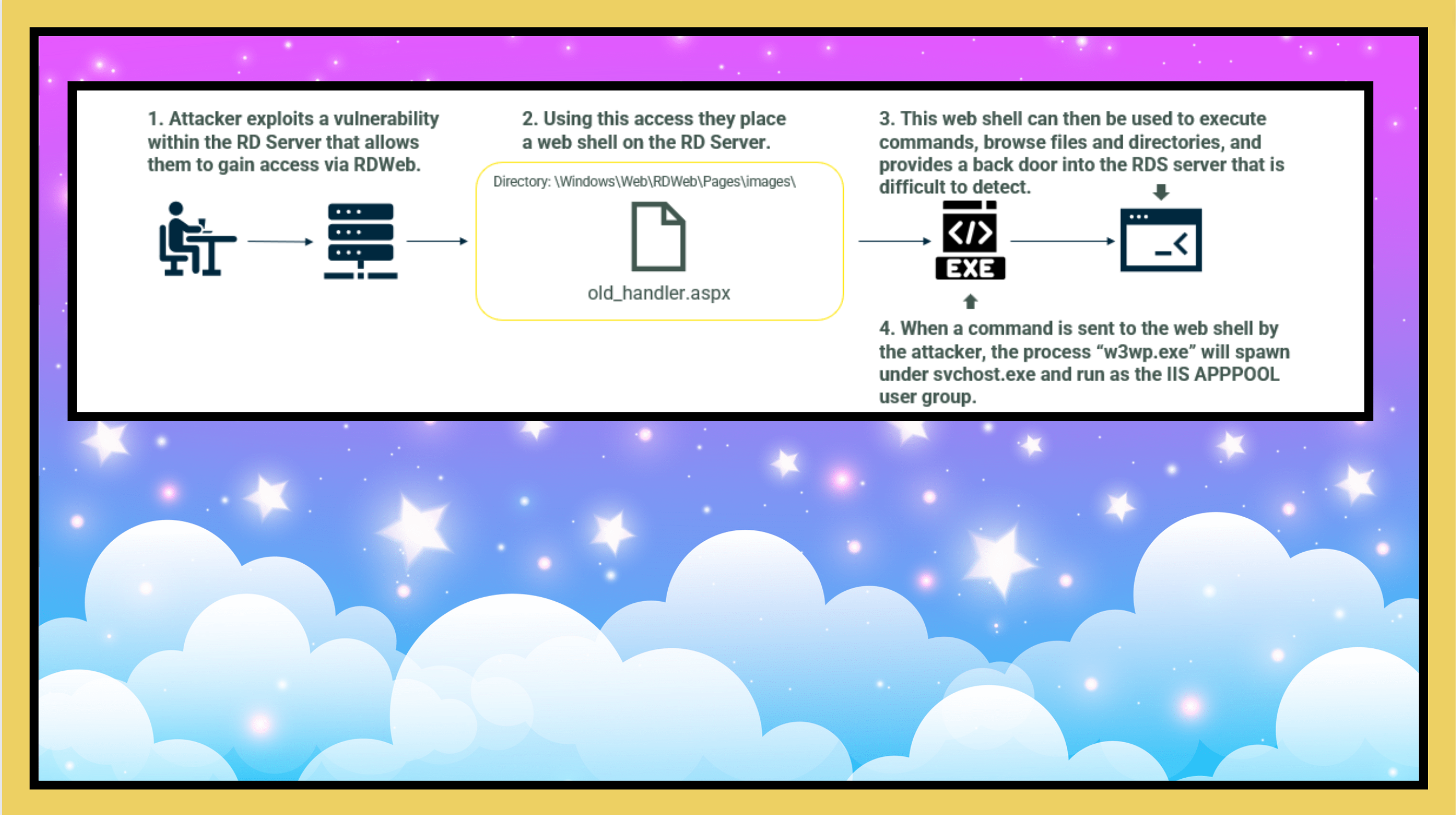

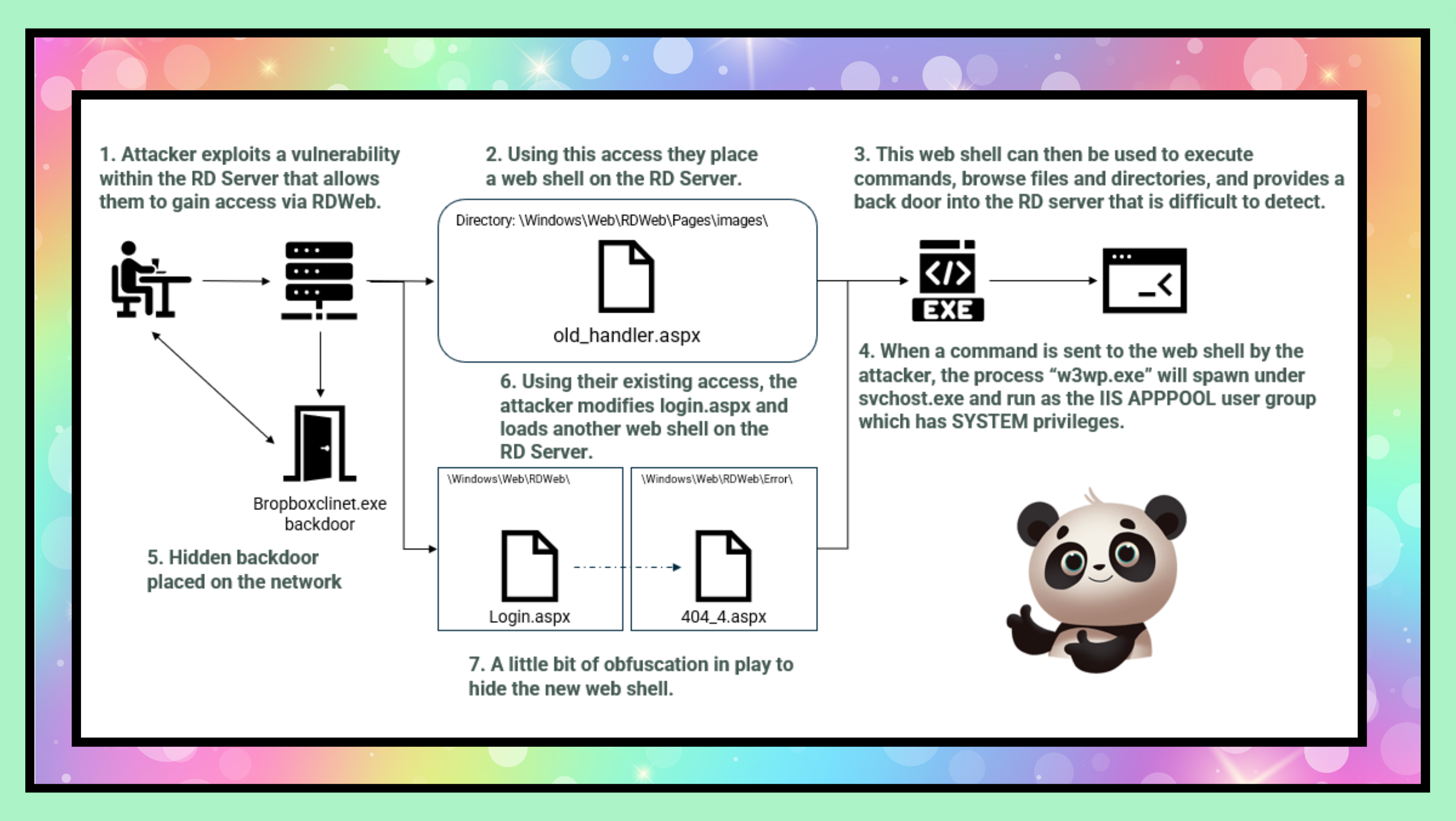

The attackers then utilised this access to gain take a further foothold and establish persistence on the server that did not rely on maintaining credentials. They installed their first web shell on day 112.

Web shells come in all shapes and sizes. They are incredibly common and powerful tools used by threat actors to maintain access to public-facing web servers. They are often lightweight, and let threat actors execute secondary payloads, escalate privileges, exfiltrate data, and move laterally within the compromised network. Web shells often go undetected due to the small footprint left during their use, an organisation’s limited visibility of their public-facing servers, and the ability for web shell-associated network traffic to blend in with normal web server activity. Because of their ease of use and difficulty in being detected, they have been and will be a favourite of threat actors for some time to come.

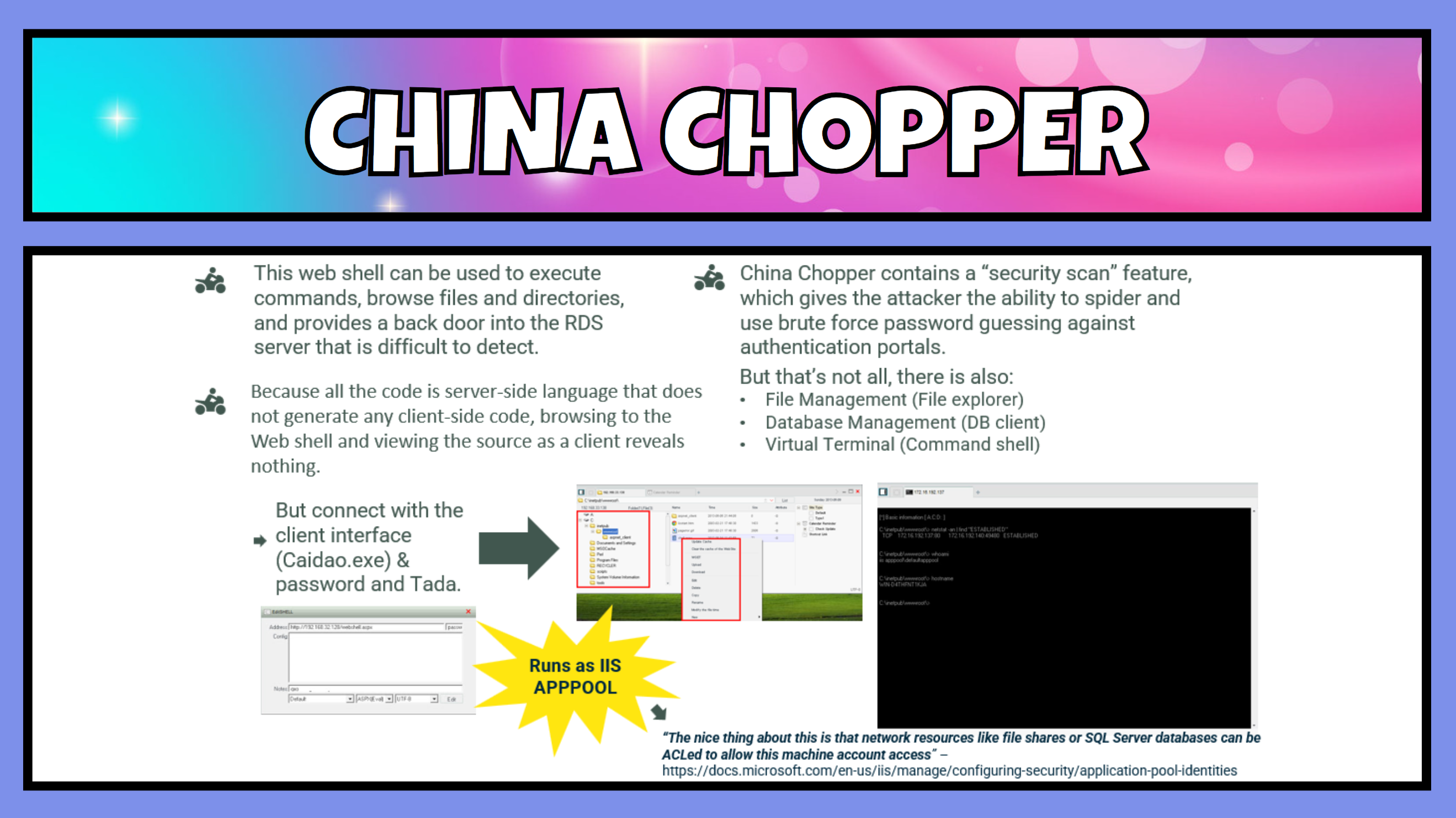

Web shells can also participate in a command and control like structure, and make browsing servers, collecting information and kicking off additional scans and tools incredibly easy to accomplish from one single pane of glass. A very popular and now quite old web shell was the first to be dropped. China Chopper.

It is important to note that while we may see connections to a web shell in web server logs, unless extending logging is enabled, the contents of the

POSTrequest to the webserver will not be recorded, so it may be impossible to determine exactly what the attacker was doing during those access periods.

China Chopper, although having an incredibly small footprint on the “server” side, i.e. the victim computer, it is quite a powerful tool. China Chopper is one line of code long, very easy to hide and disguise, and comes in at about 76 B or 4kb on disk. How can this one line of code do all these great things?

- For starters obfuscation is quite neat, if you were to browse to a file containing only the China Chopper code on a webserver, you’d be shown a blank page, making it look innocuous. Its like knowing the magic door knock to get into a bar.

- The client interface that makes the call out to the hidden line of code is known as CAIDAO.exe. This client provides a graphical user interface for an attacker to perform various functions:

- perform security scans that can spider network resources,

- perform brute force guessing attacks against authentication portals,

- file management and exploration,

- data base management and

- provide a command shell.

- The web shell runs under the IIS

APPPOOLgroup, which depending on configuration can have more than enough privileges for an attacker.

Not bad for one line of code on a web page.

The problem so far #

By day 120 the attacker had the credentials of at least 6 domain users (those they had used) and installed a web shell that provided them additional functionality to dig deeper into the network and provide persistence. There are a number of opportunities for detection so far:

- Log analysis might have revealed suspicious activities, including brute force attempts.

- Anti virus may have detected the web shell (maybe not either).

Defence evasion #

We fast forward now to around day 318. Defence evasion describes techniques that adversaries use to avoid detection throughout their compromise.

What if you could use a valid third-party application with a legitimate signature to then load a malicious payload wrapped in a DLL? That might be one way to evade detection, right? Yes, correct, it is a very cunning way to evade detection.

Want to make it even more cunning? Then hide it within an anti-virus product.

This actor used a legitimate signed binary owned by the “F-Secure” corporation, a cybersecurity company, and then side loaded a multi-stage in memory backdoor and secure command and control (C2) channel.

How this works.

- This file, fsstm.exe was a valid and genuine executable by the F-Secure company. What was not genuine was the fspmapi.dll loaded into the same directory as the executable. matches the name for the F-Secure Management Agent library.

- Whenever an executable is launched in a Windows system, the EXE file will often load secondary libraries containing executable code. These are formatted as dynamic link library (DLL) files which are loaded from trusted system paths. Typically whenever a DLL is requested by the EXE file, the default behaviour is to search a series of folders, starting with the EXE’s own folder, for any DLL that matches that name. The reason for this is that a software developer may choose to provide their own copy of a DLL file and that copy should take precedence over any provided by the system.

- This technique called DLL side-loading has been trending in recent attacks.

- DLL side-loading takes advantage of Windows’ side-by-side (SxS or WinSxS) assembly feature, which helps manage conflicting and duplicate DLL versions by loading them on demand from a common directory. The problem with this technique is that it offers little to no validation of the loaded DLL other than what is explicit in the manifest’s DLL metadata. This omission inadvertently grants trusted installer privileges to malicious payloads.

- The DLL file called fspmapi.dll called upon 2 additional payloads in the directory: data.dat and data.bin which were loaded into the memory space of the fsstm.exe service and hid cobalt strike and bespoke command and control facilities including:

- Full remote access backdoor

- Data exfiltration capabilities via HTTP, FTP and covertly via Dropbox (API)

- In memory file mapping (where files can be read from disk, in memory and encrypted to be exfiltrated)

- Ability to run arbitrary commands and delete files

- The actor used the Windows Task Scheduler (aka. Scheduled Tasks) to keep persistence with the backdoor over the course of the next 1.5+ years and distribute the malware to additional servers.

The use of DLL side-loading with the f-secure binary looks to go back as far as 2014 with APT actors using the technique to deploy Plugx RAT, with more recent usage in 2019 and more recently we have seen this in our investigations involving nation state, using the MS defender binary and library file. This was also the technique used in the Kaseya ransomware attacks in 2021.

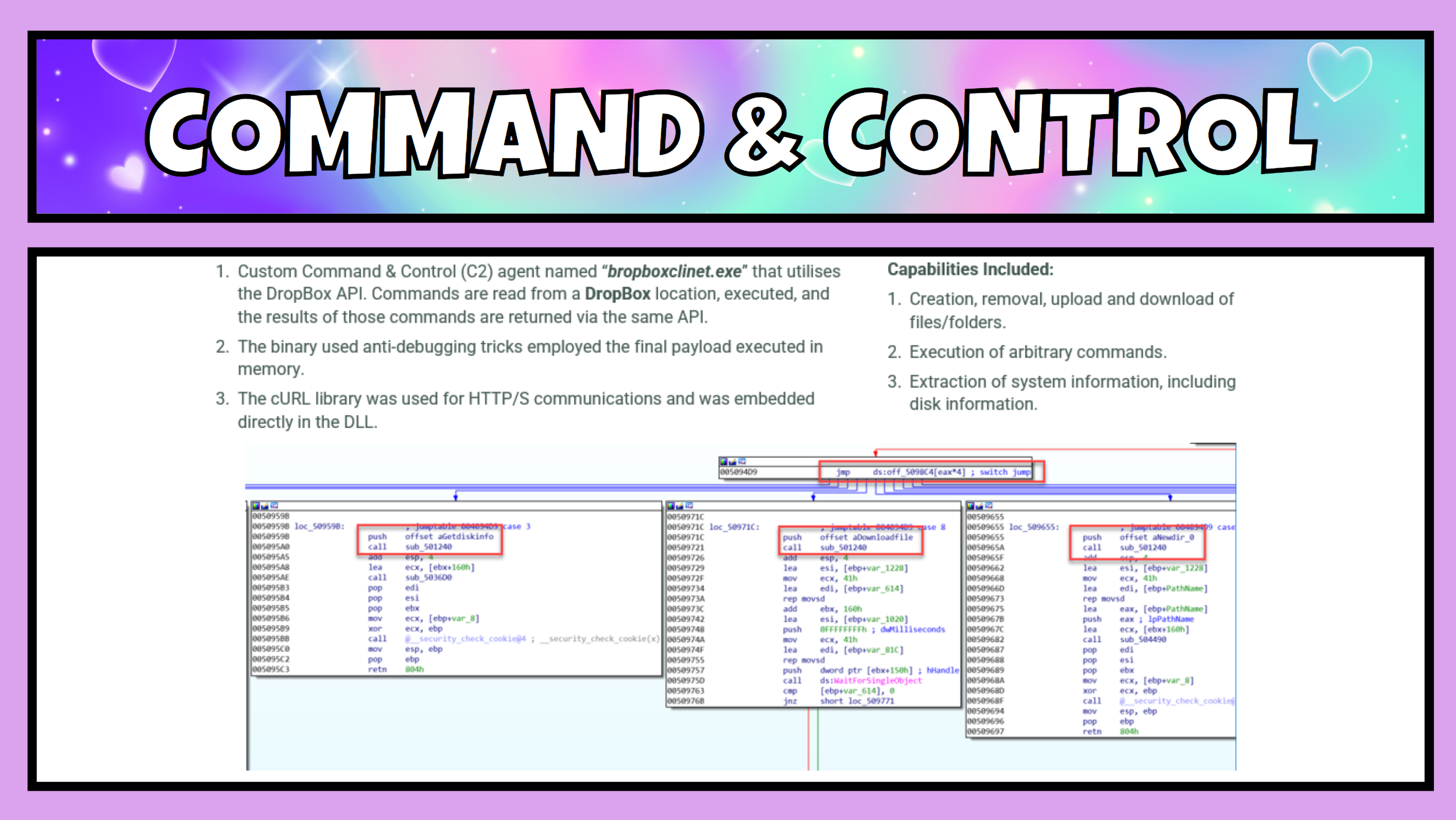

Command and control #

Within the data.dat and data.bin files loaded by the DLL was a backdoor that could create, remove, upload and download files and folders, execute commands, and extract system information. What it also contained was the attacker’s mechanism for obfuscated data exfiltration.

This backdoor once executed in memory, ran under the context of svchost.exe was a Command & Control (C2) agent named “bropboxclinet.exe”. This agent utilised the DropBox API for its communication channel. Commands were read from a DropBox location, executed, and the results of those commands were returned via the same API. Making this look like traffic to and from DropBox, and hey, we’d expect to see large file transfers to and from DropBox wouldn’t we? Including maybe gigabytes of data being “synced”. This likely would not stick out too obviously with someone looking at network usage.

The cURL library needed for HTTP/S communications and was embedded directly in the DLL. They had everything they needed within those data files to perform covert activities and we had little to no evidence of data exfiltration save information showing which directories they had browsed on the file system.

Day 431 – time to upgrade their web shell. #

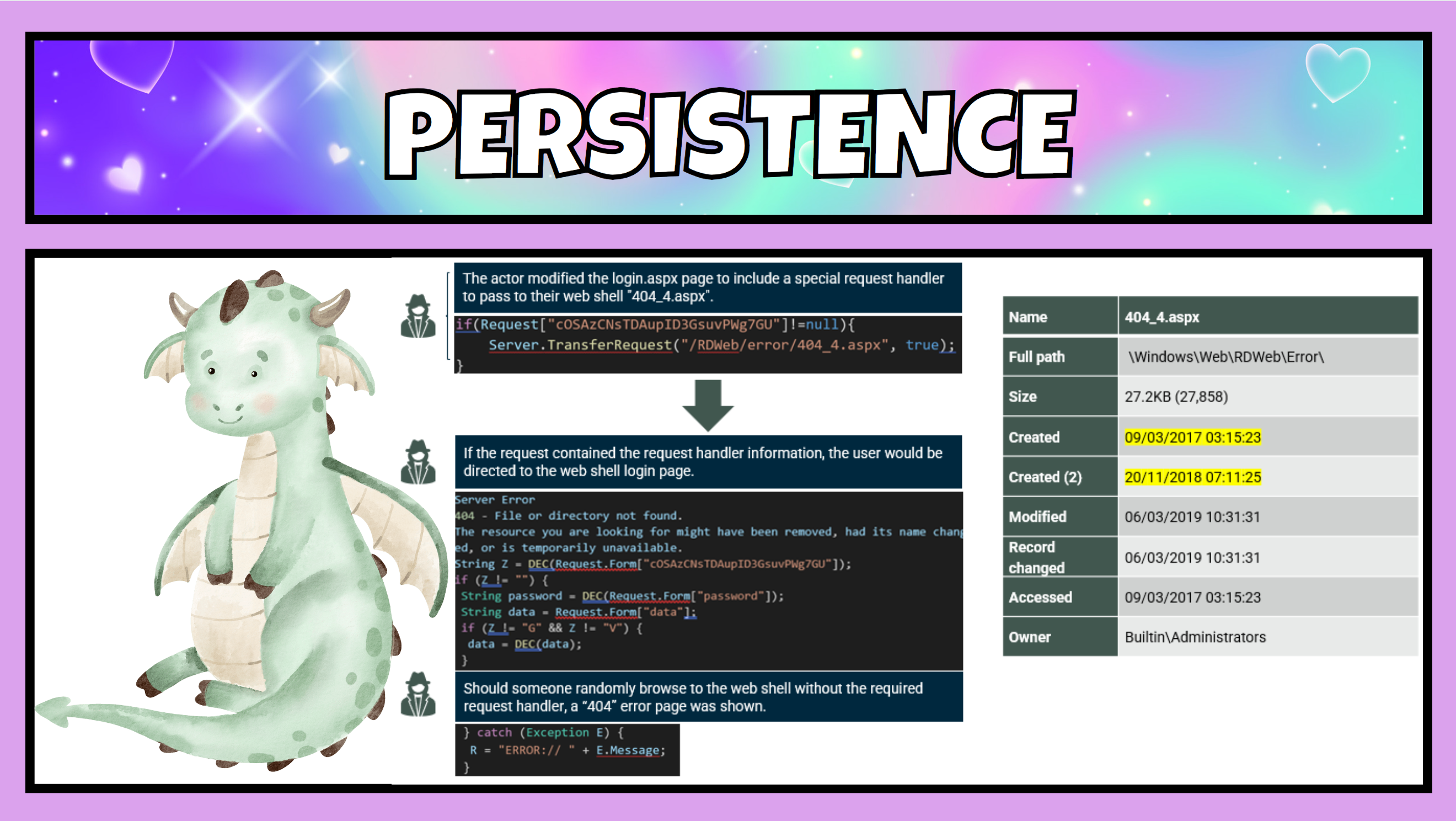

These attackers chose to install a more function rich web shell on the RD server that would enable even more functionality, such as file manipulation, execute commands, exfiltrate data, and the most notably new addition - execute SQL queries.

The first thing they did was edit and recompile the “login.aspx” file located in the RDWeb folder on the server. They modified this file with code that if a specifically crafted request was sent to the page, the request would be redirected to the newly loaded web shell – 404_4.aspx.

This giving a level of obfuscation and making the web shell more difficult to detect externally. Should someone stumble across this web shell page, then they would see a normal 404 error having not passed the required information.

Taking some extra precautions, on this web shell the attackers performed an anti forensics technique called Time Stomping.

Timestomping is a technique that modifies the timestamps of a file such as the modify, access, create, and change times, often to mimic files that are in the same folder. The attacker did this to make the file look like it had been on the system a much longer time than it had. The timestamp Created would be what is seen in Windows Explorer and should someone take a look they’d likely think that file had been there for several years, when in fact it hadn’t.

Fortunately, through the use of forensics tools to review files on a system, and ultimately take information from the Master File Table (MFT) we can see that the created times do not match and we can tell when exactly this file was placed on the server by the attacker.

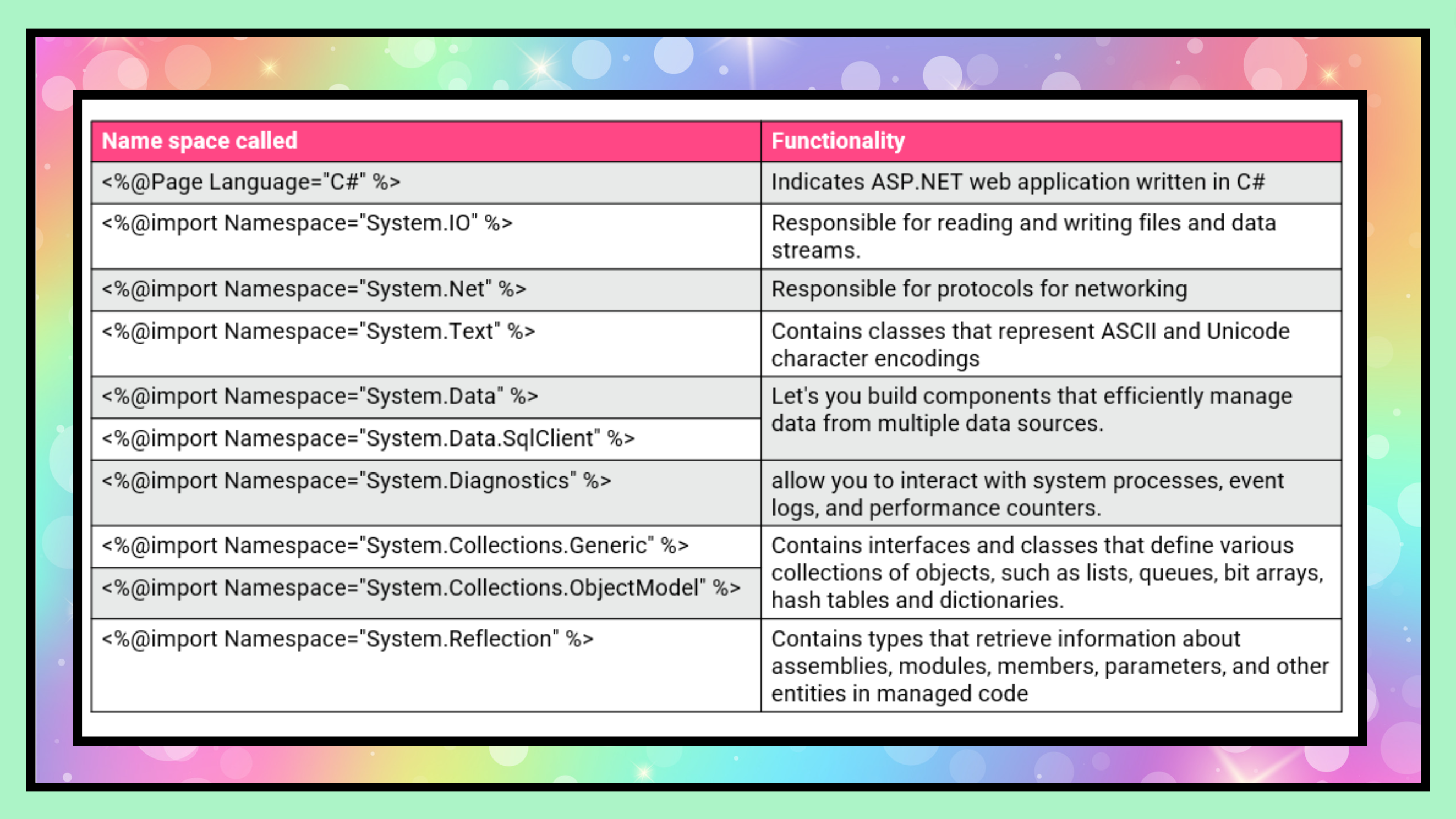

This new web shell was feature rich indeed. I’m not going to go through all these functions, but you can see that a simple web shell can be a powerful tool and provide access to systems, and functionality within them. We could hypothesise that the attacker installed the more powerful web shell as they had grown a little more confident about not being detected. It may have been that this was a slightly different attack group or even individual that had a separate mission.

In closing #

What I’ve talked through today is an example of a persistent threat.

Over 900 days persistent.

This was an attacker that ensured their access into this environment was rock solid should any single one of the mechanisms they had in place be defeated.

Attackers like this typically run `mimikatz`` frequently, update and add additional web shells, and create stealthy backdoors into an organisation. Most often utilising several different techniques to remain undetected in a network for a long period of time. They will rarely “burn” a zero day if they don’t have to, but they will when they need. Their goal is to dwell, to stick around and gather as much information as possible over the greatest length of time. You kick them out? They will try and get back in, it could be days, weeks or even years later, but if there is something that they want, they will keep trying until they get it.

We often stress that understanding the scope of an attack is extremely important, the scope will help make sure that all avenues of persistence can be identified and eradication final. We still frequently handle incidents where the attacker has been resident for more than enough time to achieve their missions several times over.

The dwell time of this attacker could have been dramatically reduced if someone was looking out for them.

Yes they had an MSSP, and no that MSSP was not looking.

Everyone wants to see less notification of breaches from third parties and of course, that dwell time number reduce for reasons other than ransomware, This will only happen if we share the knowledge of tactics and techniques as we see them and be looking out for them, so I hope that I have provided you with some food for thought on your next threat hunt, or your next offensive exercise.

Reference reading #

- https://medium.com/falconforce/the-att-ck-rainbow-of-tactics-5eb6f0bddebe

- https://informationonsecurity.blogspot.com/2012/11/china-chopper-webshell.html

- https://www.mandiant.com/resources/breaking-down-china-chopper-web-shell-part-i

- https://www.domaintools.com/resources/blog/covid-19-phishing-with-a-side-of-cobalt-strike